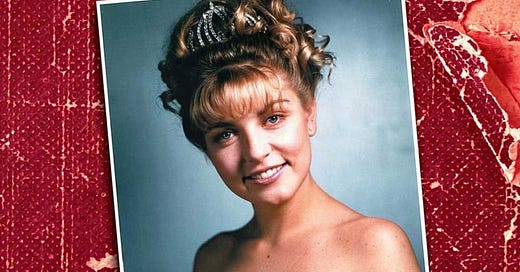

When Twin Peaks first aired in 1990, Laura Palmer was already dead. A homecoming queen wrapped in plastic, she became a symbol of mystery, of small-town rot, of feminine ruin. But in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, we meet the living Laura: desperate, dissociated, angry, erotic, and ashamed. Her voice, scrawled in pages meant never to be read, is raw and often unbearable. The diary doesn’t just tell the story of her murder. It reveals the psychology of a girl undone by complex trauma and familial betrayal, and trying, against all odds, to understand herself before time runs out.

What happens when we read Laura psychoanalytically, not just as a murder victim, but as a fragmented adolescent survivor of sexual violence? What do her writings show us about trauma, reenactment, and the split between self and shadow? What do we do with the knowledge that the monster lived at home?

Part I: Laura on the Couch

“I want to crawl inside a shell like an egg … and not come out.”

“BOB is with me in everything I do.”

From her earliest entries, Laura writes like someone observing herself from above. Her descriptions of daily life are filtered through a fog of dread, fantasy, and shame. She vacillates between childlike longing. “I wish someone would just tell me I’m okay”, and nihilism, convinced she is beyond redemption.

This instability reflects a core feature of trauma-induced dissociation, in which the psyche fragments to survive overwhelming, often inescapable harm (Spiegel et al., 2013). The disconnection Laura describes is more than emotional numbing. It is a structural splitting of identity. Modern trauma theorists frame this as a "trauma-self" and a "functional self," often at war with each other (Schauer et al., 2022). Laura’s diary oscillates between these parts. One who pleads for safety, and one who seduces danger.

“I let it happen. I wanted it to happen.”

This line, like many in the diary, reveals internalized guilt. In reality, what Laura “wanted” was connection, control, and a way to manage the horror she couldn’t name out loud. Adolescents who experience repeated sexual trauma often use fantasy, ritual, and self-blame to create a sense of coherence (Greeson et al., 2020). These internalized narratives (“I deserved it,” “I wanted it,” “I’m bad) are not uncommon; they’re survival mechanisms.

Freud might read Laura through the lens of the death drive (Thanatos), suggesting her compulsions toward sex and self-destruction are efforts to resolve unbearable psychic tension. Jung, conversely, might focus on the collapse of ego and shadow: BOB as her shadow self, her unintegrated trauma, her "dark twin." But even without these lenses, the diary’s form itself, erratic handwriting, shifting tone, and chronological ruptures mirror the chaos of dissociative identity confusion.

Laura is not lying. She is fragmented.

And the tragedy is: no one notices.

Part II: The Inheritance of Horror: Leland and BOB

In the show, BOB is framed as a supernatural predator, a demonic parasite who possesses human hosts. But the horror is far more grounded: BOB lives inside Leland Palmer, Laura’s father. Whether possession is literal or metaphorical, the result is the same. The man who should protect her is the man who hurts her. The boundary between father and abuser dissolves, leaving Laura without any safe harbor.

“BOB smells like my daddy. BOB knows things he shouldn’t. Maybe they are the same.”

This is not just a supernatural twist. It is the clearest representation of what trauma theorists call betrayal trauma. Children who are abused by caregivers often compartmentalize the abuse in order to preserve attachment; their survival depends on loving the person who hurts them (Freyd, 1996; Frontiers in Psychology, 2024). Laura’s psyche twists itself in knots trying to make sense of this: BOB is not her father, but he is. The man who brushes her hair is the man who invades her at night.

In psychoanalytic terms, Leland represents the failed paternal function. The collapse of protection into predation. For Laura, the only way to maintain psychic coherence is to split herself in return.

Part III: Sex as Reenactment

“Sometimes I can’t stop myself from wanting to be bad. I hate it. But I need it.”

Laura’s sexuality is not autonomous. It is haunted. She describes sexual encounters in which her agency is murky at best, manipulated at worst. She writes about older men, violent boys, group sex, sex for money, sex for numbness. In one particularly disturbing passage, she writes:

“I felt like a puppet. I smiled because that’s what they wanted.”

This is reenactment, not of pleasure, but of powerlessness. Adolescent survivors of CSA often report high rates of sexual risk-taking and substance use, not because they are promiscuous, but because these are tools for emotional escape and regulation (Journal of Adolescent Health, 2023; ScienceDirect, 2022). In Laura’s case, sex becomes a language she uses to say, “See me,” even when it leads to more danger.

A recent study on trauma reenactment found that adolescents with early sexual trauma often unconsciously seek out familiar dynamics, not for pleasure, but in the hope of changing the outcome (Greeson et al., 2020). Laura keeps trying to reclaim her body, but each attempt deepens her shame. She vacillates between seeking out sexual situations and punishing herself for them.

What’s worse: she knows she’s being harmed. And she believes she deserves it.

Part IV: Risk and Resilience

From a forensic standpoint, Laura Palmer was high-risk in nearly every category:

Early and repeated childhood sexual abuse by a caregiver

Substance dependence

Social isolation cloaked in performative popularity

Dissociation and severe emotional dysregulation

Ongoing exposure to sexual exploitation

These factors have been shown to increase the likelihood of depression, suicidality, revictimization, and complex PTSD by significant margins (Mental Health Journal, 2025; OBM Neurobiology, 2023).

And yet, Laura wasn’t entirely unprotected:

She had strong moments of introspection and critical thought (“BOB isn’t just outside me. He’s in me.”).

Her diary was a form of narrative therapy. An attempt to make meaning from chaos (Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2024).

Her friendships, though fractured, occasionally grounded her in something real.

Still, the scales were tipped. The systems meant to support her failed. Dr. Jacoby’s ineffectiveness, the adults who didn't ask questions, and the pervasive silence that blanketed her home.

TF‑CBT could have helped. It remains the gold standard for treating trauma in youth and shows strong outcomes in reducing PTSD, shame, and self-harm behaviors (SagePub, 2023). It’s a model that prioritizes stabilization, narrative construction, and integration. All things Laura tried to do on her own, with a pen.

Part V: The Town That Looked Away

“Maybe if someone really saw me… they would know. They would stop it.”

This is the heart of the tragedy. Laura wasn’t invisible. She was hypervisible. She was on posters, at dances, in therapy, in church. Everyone saw her smile. No one saw her bleeding.

Twin Peaks is not just about mystery. It’s about complicity. The town needed Laura to be the golden girl. Her beauty was currency. Her pain was inconvenient. Like many real-world victims, she was loved in the abstract but abandoned in the moment of need. Her father was respected. Her suffering was inconvenient. Her silence kept everything tidy.

The town looked away until it was too late, and then mourned her like a saint.

But she knew. She told us. Over and over.

Why Laura Still Haunts

Laura Palmer is not just a mystery to be solved. She is the embodiment of what happens when trauma goes unspoken, when predators wear the face of love, when girls are trained to smile through pain. Her diary is not just a narrative device. It’s a scream, a plea, a blueprint of a mind trying to survive the unthinkable.

Psychoanalysis tells us that the repressed always returns. In Twin Peaks, it returned in Laura’s voice. In the diary, in the Red Room, in the whispers of the woods. But in real life, too, the repressed returns in survivors who carry shame that isn’t theirs, in communities that prize silence over truth, in systems that punish pain with invisibility.

Laura Palmer haunts us not because she died, but because she was never really seen while alive.

References

Between pleasure, guilt, and dissociation: How trauma unfolds in the lives of adolescent girls. (2023). Journal of Adolescent Health, 72(4), 567–579.

Dissociation (Psychology). (2025). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 2025.

Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal Trauma: The Logic of Forgetting Childhood Abuse. Harvard University Press.

Greeson, J. K. P., et al. (2020). Reenactment and risk: CSA, adolescence, and coping. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(17–18), 3115–3135.

Lynch, J. (1990). The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer. Pocket Books.

Mental Health Journal. (2025). Childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of CPTSD: A meta-analysis. Mental Health Journal, 15(1), 1–12.

OBM Neurobiology. (2023). Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy outcomes in youth. OBM Neurobiology, 6(4), 146–159.

SagePub. (2023). Meta‑analysis of Trauma-Focused CBT with 12‑month follow-up. Child Abuse & Neglect, 125, 105–116.

Schauer, M., Neuner, F., & Elbert, T. (2022). Narrative Exposure Therapy: A Short-Term Treatment for Traumatic Stress Disorders. Hogrefe.

ScienceDirect. (2022). Risky sexual behavior in trauma-exposed adolescents. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(2), 123–136.

Spiegel, D., et al. (2013). Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 299–326.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. (2025). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 2025.

Frontiers in Psychology. (2024). Betrayal trauma and attachment disruption. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1364001.

Frontiers in Psychiatry. (2024). Narrative therapy with adolescent survivors of CSA. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1147555.